Music Note Values

Each music note written on the stave has a duration (length) as well as pitch. It is the design of the note that tells you its duration, in the same way as the position on the staff tells you the pitch. So each music note on a stave gives you two pieces of information, pitch and duration. This page focuses on the duration of each note.

The Rhythm Tree

In order to fully understand note lengths become familiar with the rhythm tree. Click here to learn more about the rhythm tree before continuing. The rhythm tree shows how the notes are related to each other.

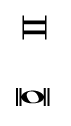

Double Whole Note (Breve)

Although the whole note is the longest note we generally use today, as

is hinted at by the UK name there used be a note called a Breve. This is

known as a Double Whole note in the US. The double whole note (breve)

divides into 2 whole notes (semibreves) following the pattern of the

other notes in the Rhythm Tree. The Double Whole note (Breve) is

therefore worth 8 quarter notes (crotchets). The Double Whole note

(Breve) fell out of use as smaller value notes were invented by

composers. It can be notated as an open rectangle or a whole note with

bars either side.Click here to read more about the double whole note (breve)

and how our modern system of music notation developed. Make sure you

have a few spare moments though as once you start reading the history of

the music note it's difficult to stop!

Whole Note (Semibreve)

The Whole note is the longest music note in general use today. It is an

open note with no stem. I always say to my students it looks like a

hole…so it is easy to remember! The duration of the whole note is 4

quarter notes.

Half Note (Minim)

The Half note duration is 2 quarter notes. It differs from the whole

note in that it has a stem, although it is still open. For students I

liken this stem to the line in the middle of the ½. This also helps them

remember that 1 half note is worth 2 beats (in 4/4 timing, which is

what they are usually working in when learning this).

Quarter Note (Crotchet)

The quarter note has become the de facto standard 1 beat music note.

This has happened as the 4/4 time signature is the most popular (with

3/4 and 2/4 following close behind) and quarter notes have a duration of

1 in these time signatures. It is also roughly in the middle of the

most used notes in the Rhythm Tree,

making the quarter note the ideal candidate for ensuring whole notes

don't become too long to count, and shorter, popular notes such as

eighth and sixteenth notes aren't impossible to count in terms of them

being fractions of a note. The quarter note changes from the half note

as it is filled in, as opposed to empty.

Eighth Note (Quaver)

The eighth note is worth ½ of a Quarter note. It may also be considered as a one beat note in 3/8 and similar timings, the 8 on the bottom of the time signature giving the clue that you are counting in eighth notes. This is the first note in the rhythm tree to have a flag. The flag is the name for the 'tail' added to the eighth note. Eighth notes may be a single as shown on the left, or joined together with beams.

It is common to see eighth notes joined into sets of 2 to make one beat.

Eighth notes may also be grouped in 3s, 4s, 5s, or even 6s depending on

the time signature. Remember, however, that no matter how many eighth

notes are joined, each one is worth half a quarter note.

Sixteenth note (Semiquaver)

The Sixteenth note is worth ¼ of a Quarter note. It may be beamed together in the same way as the eighth note. It changes from the eighth note by having an additional flag. Look at the picture and you see a double flag at the top of the stem. This is how you tell a note is a sixteenth note.

Sixteenth notes may be beamed together in the same way as Eighth notes.

When you see sixteenth notes beamed together each note has a double

flag. Here is an example of 4 Sixteenth notes beamed together, they are

also common in groups of 2.

Mix and match different music note values

Eighth and sixteenth notes (and other music notes with flags) may be joined together. The key to knowing which note you are dealing with is very simple look at the number of beams joined to the stem of the note. By counting the beams joined to the stem of the note you will always know what type of note you are looking at. In the examples below you can clearly see how this works.

In this example there are 2 Sixteenth notes (2 beams touching the stem) joined ot an Eighth note (1 beam touching the stem)

In this example there is 1 Eighth note (one beam touching the stem) joined to 2 Sixteenth notes (2 beams touching the stem)

This is a note grouping that often confuses people, but it needn't! It

is simply 1 Sixteenth note (2 beams on the stem) joined to an Eighth

note (1 beam on the stem) joined to another Sixteenth note (2 beams on

the stem!)

You may also have noticed that the three grouping examples above

all add up to 1 Quarter note!

Thirty Second Note (Demisemiquaver)

This is the point at which it becomes more fun to learn the UK music

note terminology! The thirty-second note has 3 flags and may also be

beamed together in the same way as the Eighth and Sixteenth notes.

Sixty Fourth Note (Hemidemisemiquaver)

As a young music student I never tired of the name hemidemisemiquaver,

and for this, if nothing else, I am glad I learned the UK version of the

note names rather than the US version. Hemidemisemiquaver just sounds

so much more fun than Sixty-fourth note! The Sixty-fourth note has 4

flags and is the shortest note in general notational use. It may also be

beamed together. The name hemidemisemiquaver actually makes sense if

you look at it. Each part of the name is the word for 'half' in Greek

(hem), French (Demi) and Latin (Semi). So a hemidemisemiquaver is half

of a half of a half of a quaver (eighth note)... i.e., a Sixty-fourth

note!

A Clear Path To Learning Music Theory

For more help check out my new theory book Essential Music Theory: Learn To Read And Appreciate Music Vol. 1 available for iPad and Mac OS.

- A simple step-by-step course that takes you from complete beginner to grade 2 music theory

- Multi-faceted learning - audio, video, mind maps, clear musical examples

- Built in quizzes to check your understanding

Click here for more information.

Or get it on the iBooks Store!

Return to the Essential Music Theory Homepage from Music Note Values